The Five Non-Negotiables: Building Teams That Actually Work

A team of 15 failed because one person couldn't say three words: "I need help." A student wasted an entire semester because a professor couldn't admit "I don't know." A startup ground to a halt every time someone took a few days off because nobody taught anyone else how things worked.

I've spent 25+ years building technology teams—from startups that got acquired to enterprise transformations at trillion-dollar firms. I've watched brilliant people fail in predictable ways, and I've learned what separates teams that thrive from those that collapse under their own dysfunction.

Every failure comes back to the same five non-negotiables:

- Every team member must be able to say "I don't know"

- Must be able to say "I need help"

- Must be able to say "Let me show you how"

- Must be willing to suck at something new

- Must be willing to share work in progress

These aren't aspirational values to put on a poster. They're the operating system for high-performing teams. While these principles started in tech, they apply anywhere people build complex things together—whether you're shipping software, designing medical devices, or managing supply chains.

The Problem with Tech Culture

Silicon Valley worships the myth of the 10x engineer—the lone genius who codes through the night and ships miracles.

Yes, exceptional individual contributors exist. But they're usually 10x because of their systems, tools, and judgment—not just raw brainpower. Building a team strategy around finding mythical lone geniuses is a recipe for failure.

This mythology creates teams where people fake expertise to avoid looking weak, asking questions feels like admitting incompetence, and everyone waits for perfection before sharing work. Knowledge gets hoarded as job security. Single points of failure. Innovation that dies because nobody wants to look stupid trying something new.

The 10x engineer myth doesn't scale. Systems thinking does.

Why These Five Principles Work

1. "I don't know" creates psychological safety

Complexity has outpaced any individual's ability to master it. Nobody fully understands the stack anymore. Cloud infrastructure, distributed systems, machine learning, security, compliance, blockchain—each is a career-long specialization.

We pretend to know because we think we're supposed to be masters. But that pretense is dangerous.

At Berkeley, a student approached a professor with a complex problem. The professor gave a quick, confident answer. The student spent an entire semester trying to make it work—struggling, debugging, convinced he was missing something obvious. At the end of the semester, exhausted and defeated, he went back to the professor and declared himself stupid for not being able to solve it.

Only then did the professor admit: "Oh, I didn't actually know the answer. I was just guessing."

One moment of false confidence cost a student a semester of effort and his self-esteem. Multiply that across every interaction in a company, and you see why intellectual honesty matters.

The developer who admits "I don't know if this security implementation is correct" triggers help that prevents a breach. The architect who says "I don't know if this scales" triggers load testing that prevents downtime.

False confidence is a liability. Intellectual honesty is a risk management tool.

2. "I need help" builds resilience

My first robotics project: a team of 15 people building autonomous robots. We assigned the hardest technical problem—Kalman filter-based SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping)—to our strongest mathematician. He got the math right but had no idea how to translate it into working code. Too proud to ask for help.

Tournament day arrived. His code didn't even compile.

A team of 15 failed because one person couldn't say three words: "I need help."

Isolation erodes judgment. When you're stuck, your perspective narrows. You miss obvious solutions. You make trade-offs that seem reasonable in isolation but are obviously wrong to anyone with fresh eyes.

A practical rule: If you're stuck for more than 15 minutes, you must ask for help. This doesn't mean you haven't tried—it means you've hit the point where fresh eyes will solve it faster than continued solo struggle.

3. "Let me show you how" scales expertise

In my first startup, we had the dream team: brilliant frontend developer, backend engineer, systems architect, UX designer. Everyone was world-class at their specialty.

Then someone took a few days off. The entire company stopped.

Nobody knew how anyone else's work actually functioned. We'd built a team of brilliant specialists who couldn't cover for each other. Every absence became a bottleneck.

The bottleneck in every growing organization is knowledge transfer. You hire smart people, but they can't be productive because the critical knowledge lives in a few people's heads.

Documentation is necessary, but it's passive knowledge. Teaching is active knowledge transfer. When experienced people treat teaching as part of the job—not a favor or a distraction—knowledge spreads organically. The person who learns becomes the person who teaches the next hire.

And here's the secret: teaching clarifies your own thinking. The act of explaining forces you to confront your assumptions, fill gaps in your mental model, and simplify complexity.

4. "Willing to suck" enables innovation

In early-stage startups, you can't hire experts for every short-term technical need. You hire for broad skills and potential, then teach people what they need for the immediate work—fully knowing you might pivot away from that skill or business direction at any moment.

Every expert was once terrible. Every senior engineer wrote garbage code. Every architect over-engineered their first system design. Every CTO made hiring mistakes and burned months on dead ends.

Mastery is the byproduct of repeated failure. But if failure feels unsafe, people stick to what they know. They avoid stretch assignments. They stop growing.

Here's the nuance: When you're exploring new territory, messy is expected. When you're executing known work, quality is non-negotiable.

Don't punish someone for writing ugly code while learning a new framework—that's exploration. Do hold them accountable for shipping broken features to production—that's execution. The distinction matters.

I've worked with teams that celebrated "fail fast" so recklessly they shipped nothing that worked. That's deadly. The point isn't to fail; it's to be willing to be imperfect while learning something new that will eventually lead to excellent work.

5. "Share work in progress" accelerates feedback

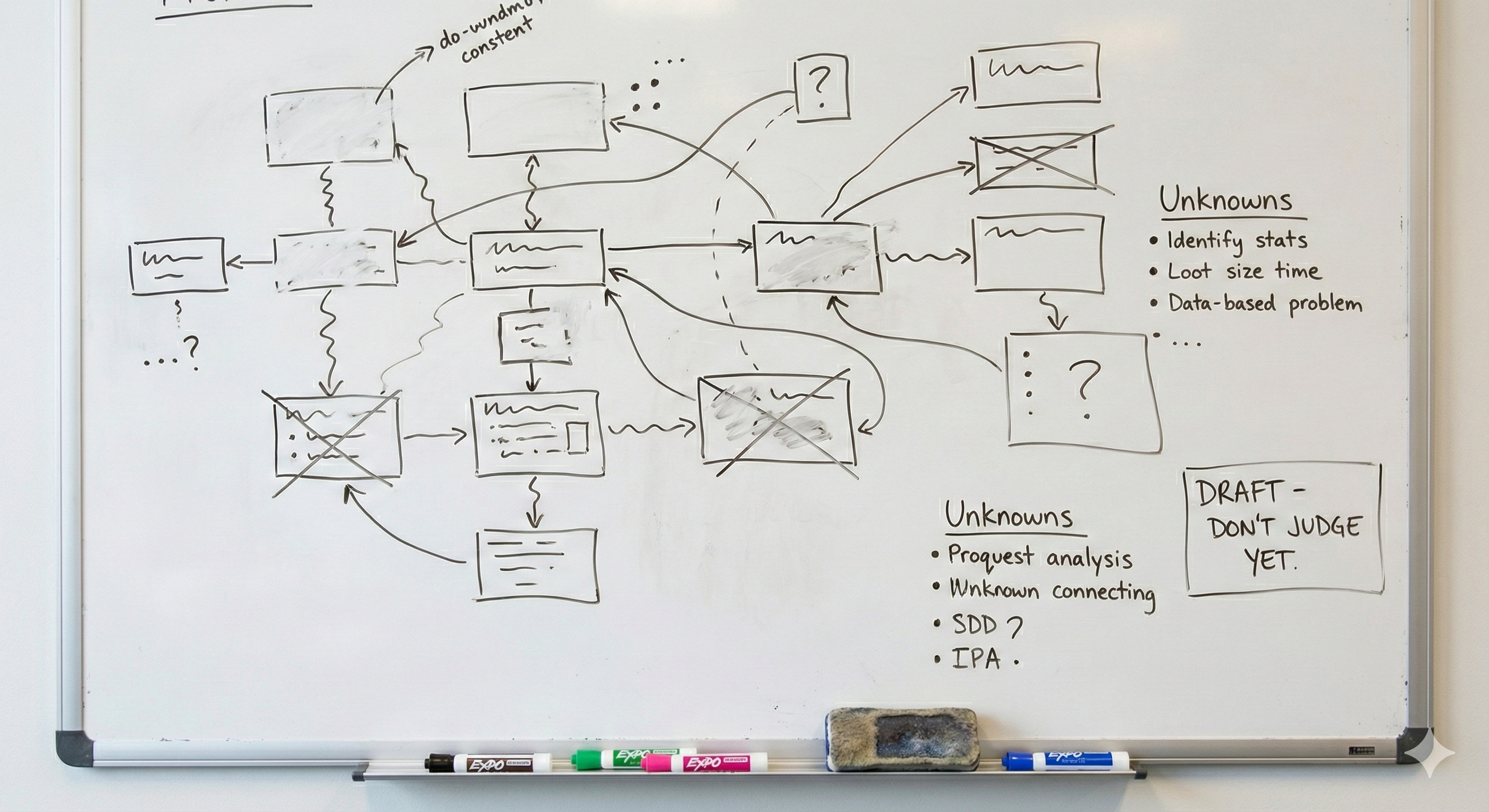

My favorite quote: "Two weeks of hacking can save you 20 minutes of drawing."

It's a joke, but it captures a painful truth. People skip the quick sketch and dive straight into building—then waste weeks building the wrong thing.

Here's how it should work: We discuss the why. Someone grabs a thick Sharpie and printer paper and sketches the architecture—ugly, fast, impossible to over-detail. These rough sketches don't create ownership or stubbornness because nobody's invested hours making them beautiful. We discuss principles first.

During this "ugly" phase, only technical peers should critique the mechanics. Business leaders should validate the direction. Why? Because business leaders often don't grasp why something was hard or what constraints existed.

Then someone tries to make it happen. They share their progress—rough, incomplete, maybe heading in the wrong direction. We learn together whether we're on the right path or need to adjust. Once we've validated the approach with working code, then we can create detailed digital architectures or polished UIs.

A Sharpie sketch reviewed in ten minutes saves two weeks of building the wrong architecture. A rough prototype shared on day two catches the fatal flaw before any polish happens.

What Leadership Looks Like

These principles don't happen by accident. They require active, intentional leadership.

Model the behavior. Say "I don't know" in meetings. Ask for help publicly. Show your draft work. Try new things visibly and badly. If you're the senior-most person and you're faking omniscience, everyone else will too.

Celebrate the behavior. When someone admits they don't know, celebrate their honesty publicly. When someone asks for help, drop everything to respond. When someone teaches, get leadership to recognize it. When someone shares work in progress, make a viewing party out of it.

Address cultural violations immediately—and often publicly. This sounds harsh, but here's why it works: In great teams, I give almost all feedback in front of everyone. Not to make one person smaller, but to grow everyone at the same time.

This is about behavior correction, not status enforcement. Psychological safety comes first—but safety doesn't mean avoiding feedback. It means creating an environment where feedback helps everyone learn.

When I correct someone's false confidence publicly, I'm teaching the whole team that intellectual honesty is valued here. When I call out knowledge hoarding, everyone learns that teaching is expected.

It's a learned skill, and you will suck at it the first times you try it. The key is tone: firm but not cruel, direct but not personal, focused on the behavior and its impact on the team.

"Hey, I notice you gave a confident answer just now, but I don't think any of us actually know that for sure. Let's say 'I don't know' and figure it out together"

That teaches more than a private conversation ever could.

Make it structural. Mandate Sharpie architecture sessions before any significant work begins. Create dedicated teaching time. Make "showed work in progress" a checkbox in your definition of done.

Adapting to Context

These principles aren't rigid rules—they're intentions that adapt to reality.

The intent remains constant: truth-telling over face-saving, collaboration over isolation, teaching over hoarding, learning over stagnation, iteration over perfection.

The method adapts:

In teams recovering from toxic cultures: Start with private feedback to rebuild trust. Public correction can re-traumatize people who've been publicly shamed before. Earn trust first, then gradually introduce public teaching moments over 6+ months.

In remote teams: Public feedback via text can feel harsher without tone and body language—use video for real-time feedback.

The goal isn't to follow these principles dogmatically. It's to preserve their intent while respecting the humans implementing them.

Signs It's Working

How do you know these principles are taking hold?

- More questions in standups and planning meetings

- People volunteering for unfamiliar tasks

- Faster cycle times from idea to shipping

- Lower turnover and burnout

- Junior people contributing architectural ideas

- No single points of failure when someone's out

The Compact

This is the deal I make with every team I build:

You agree to operate with intellectual honesty, ask for help, teach others, try new things badly, and share messy work.

I agree to never punish you for not knowing, always make time to help, recognize teaching, celebrate attempts, and give kind feedback on drafts.

The result: A team that learns faster, ships better, and doesn't burn out pretending to be superheroes.

These aren't soft skills. These are the operational practices that separate high-performing teams from dysfunctional ones.

You can have the best talent, the biggest budget, and the most exciting product. But if your culture punishes intellectual honesty, isolates people who need help, hoards knowledge, punishes failure, and demands perfection before sharing—you'll ship slower, make worse decisions, and lose your best people to burnout.

Culture isn't what you say in all-hands meetings. It's what you tolerate in daily interactions.

What does your team tolerate?

Publish November 2025